From the mid-nineties to 2004, Sardinia was our preferred summer destination. We soon became fascinated with its sacred wells & menhir sanctuaries, and explored the island “lungo e largo,” searching for little known sacred sites and remnants of Nuragic culture. Upon request, I will be publishing here a few notes from our journeys, and old photos, some pre-digital, of our discoveries. — Rome 31 July, 2022

After visiting Sardinia in 1921, D.H. Lawrence recorded his impressions of his journey in Sea and Sardinia. His brief tour of the island was a restless quest for inner renewal, a search for a rugged landscape mirroring the primordial potencies of the human soul. Wherever he traveled— Mexico, Australia, Italy, — Lawrence sought out the remains of vanished cultures which he believed had achieved a wholeness of being long forsaken by our mechanized civilization. To Lawrence, Sardinia was a place of rebirth and self -discovery, leading us “back, back down the old ways of time.” (1) Although he saw nothing of the island’s extraordinary archaeological sites, he grasped its untamed essence. “Sardinia is like nowhere. Sardinia, which has no history, no date, no race, no offering. It lies outside the circuit of civilization… Sure enough it is Italian now, with its railways. But there is an uncaptured Sardinia, still.” (2) Those closing words written a century ago still hold true today.

Sardinia does seem to lie outside the circuit of civilization. Many of the great cultural currents of the past– wars, plagues, artistic movements–seem to have grazed it but marginally. Yet it is by no means devoid of history, particularly ancient and pre-history. The island of Sardinia may be best described as an open air archaeological museum, for its circumscribed terrain is a densely- packed stratification of ruins: prehistoric, megalithic, Phoenician, Roman, early Christian, which only in recent times have been excavated.

Studies of these sites have revealed that an indigenous Bronze Age culture evolved in Sardinia, distinguished by a specific type of giant conical fortress-temple found only in Sardinia, called a Nuraghe, hence the name Nuragic culture given to the builders of these structures. This fierce shepherd people endured from 1800-500 B.C. and were gradually subdued first through the Phoenician colonization and later by the Roman occupation of the island.(3)

Sardinia possesses an abundance of sacred sites dating from prehistoric times to the First Millennium, which are unique not only in Italy but in all of Europe. In Lawrence’s day, these sites were mostly hidden beneath pastureland and wheat fields. Even today, as farmers plough fields and bulldozers raze the land for new building areas , menhirs and Bronze Age tombs are frequently unearthed. The curious tourist will find descriptions in guidebooks of the more famous monuments, like Monte D’ Accodi near Sassari , an earthwork altar akin to the Babylonian Ziggurat, but there are hundreds of minor sites, including menhirs, dolmens, temples, and sacred springs, many uncharted on maps, located on abandoned farmland.

Means of transportation to Sardinia from the Italian mainland have greatly improved since Lawrence set out at dawn with a thermos of coffee to cross from Civitavecchia to Palermo and on to Cagliari. Nowadays, high powered ferries take you from Civitavecchia to Golf Aranci on the northern tip of Sardinia in only three short hours. Upon arriving, visitors are still met by the resinous fragrance of rock roses growing along the cliffs. Then, heading south away from the built – up resorts, you find yourself in a time warp. Alone on an empty highway, you drive inland through deserts of stone alive with chattering cicadas. Here loom huge rock formations twisted into monstrous shapes by the forces of erosion. Here, just a few miles off the road, menhirs and dolmens bear testimony to a human presence of staggering antiquity.

The prehistoric peoples who created these monuments were shepherds and worshipers of the Great Mother. At intervals during the year, they made collective pilgrimages to various sanctuaries or places of power located throughout the island, where they met with clans from other areas. This was a pattern of social aggregation recorded up through Roman times. Stones were the signature and earthly vehicle of the Great Mother and of the other divine forces with which pilgrims sought to come into contact while visiting a sanctuary. Higher powers spoke to human beings through menhirs, dolmens, water, and earthworks.

At some point in the early Bronze Age, the focus of the local religion shifted from stone to water, a shift reflected in a new preference for sacred wells as the locus of religious ritual. Some scholars claim that this change came about due to the discovery of paternity and of the role played by the vivifying waters of semen in the act of procreation. The springs feeding these wells were held sacred for their power to guarantee fertility, and their fecundating capacity is celebrated by legend and folk practices. These springs are also still believed to possess healing powers.

Forty Nuragic well – sanctuaries have been found in Sardinia. Although these sanctuaries may include other architectural structures, such as tombs or nuraghi, the heart of the sanctuary is always its sacred well. These wells all conform to the same architectural design: an underground dome- shaped chamber, or tholos, containing the well, and a stairway giving access from ground level to the subterranean chamber. The sacred well of Santa Cristina near Cabras in the province of Oristano on the western coast, is the best preserved example and the easiest to visit for it is situated in an archaeological park just off a main highway. Here, menhirs, nuraghi, and other ruins lie scattered in a field where sheep and goats graze under the shade of carob trees. The only sounds you hear while wandering through the park on a summer afternoon are the tinkling of sheep bells, the rustling of weeds, and the cars whizzing past on the highway.

A Visit to Santa Cristina

The park is divided into three distinct zones, the ritual area, where the well is located, a nuragic village where dwellings once stood, and a medieval religious village and church, now abandoned. The structure enclosing the well itself was built around 1700 B.C., but the site was probably used as a sanctuary at an even earlier date.

A stalwart couple of rough-hewn menhirs blistered with ochre lichen stand at the entrance to the village. In the Sardinian imagination, these stone guardians are sexed: the woman is the plumper one transfixed with a hole, the man, somewhat smaller, stands at her side. Together they emanate a palpable presence and watchfulness. Over the centuries, menhirs continued to be linked to the ideas of fertility and sexuality even in Christian times, and medieval legends of similar menhir couples on the island claim that they are the petrified figures of monks and nuns, escaping together from the celibacy of the convent.

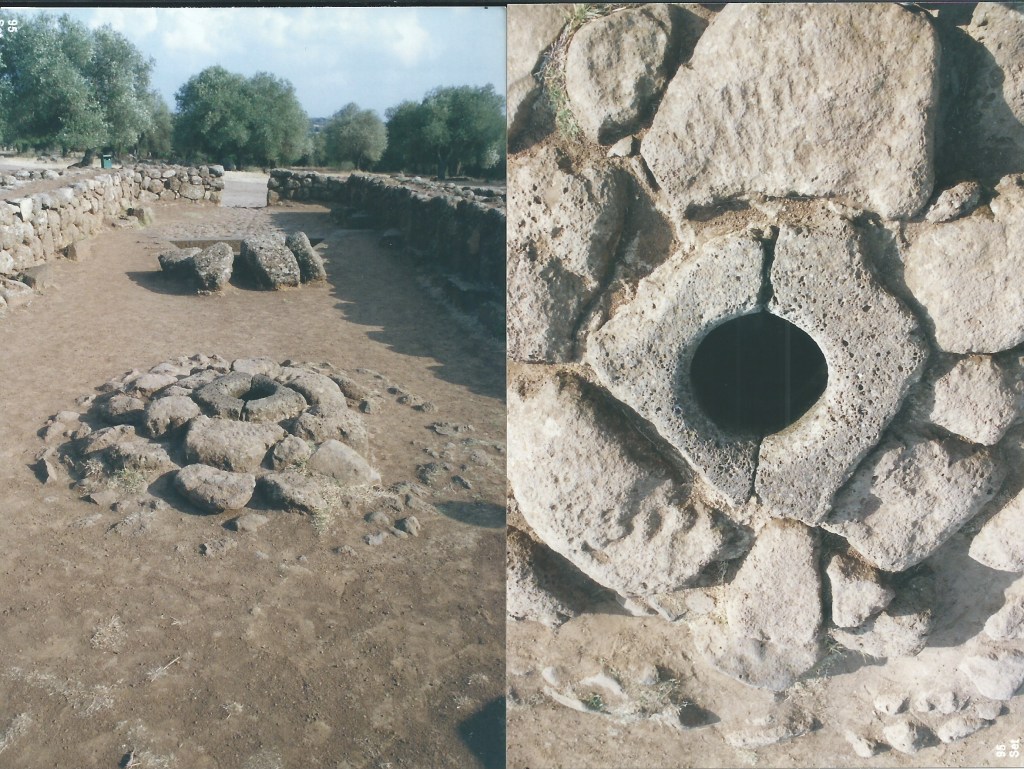

Crossing the village and approaching the sacred area, you come upon a circle of stones elongated on one end in a shape resembling a keyhole. In the center, a smaller circle of stones borders a dark hole in the earth. Peering down into this shaft you see only pitch blackness. A few feet away there is another, larger trapezoidal- shaped opening where a steep staircase made of stone blocks cut with extraordinary precision leads down into the chamber. This is the entry into the body of the Mother.

The staircase penetrates into the subterranean womb containing the well: a circular pool brimming with greenish water, dimpled by larvae and tiny insects. Descending the stairs, you will note that this is not stagnant rainwater, for the surface is neither putrid nor covered with scum. The spring that once fed the sacred pool three thousand years ago still keeps it bubbling faintly today. Across the millennia countless people have come to contemplate this pool, to touch or drink its water, all looking for the same authentic source, the same healing power.

It will take a moment for your eyes to adjust, but if you go all the way down to the rim of the pool, a remarkable phenomenon becomes visible. A circle of light bounces into view, like a large bubble floating on the murky water, reflecting a shining patch of blue sky, for there is a hole in the very top of the dome, like a giant eye gazing upwards to receive the light. That hole is the opening to the shaft you see on ground level. Everything that passes before it: a drifting cloud or a bird’s jagged flight, someone’s face looking down, a hand waving, is reflected in the pool below where the image, slightly enlarged, appears uncannily clear as in a burnished mirror. As I gaze into the mirror, a jet streaks by overhead.

Studies have shown that this particular opening is oriented to reflect the full moon of the spring equinox every 18.6 years. It is to be underlined that the culture that produced this well has left behind no trace of any systems of writing or mathematical notation.

No one knows whether the rites performed in the wells were of a communal or individual nature. Did a priest descend those stairs alone to commune with the moon’s reflection. Or did individuals go down one by one to perform a more personal and private rite? Perhaps they were granted some special vision or oracle of the gods, projected down through the opening above. Such a spectacle performed at night, with glimmering torchlight reflected in the well, would no doubt have had a powerful psychological effect on the participant. Very little is known about the religious practices of these indigenous Sardinians. We do know that they quickly adopted to the Phoenician and Roman gods, and that under Phoenician rule, this same site was used by worshipers of Demeter and Kore.

Huts sprang up around the well offering lodgings to visiting pilgrims. Over time the huts became a village, Sardinia was Christianized, and the church of Santa Cristina was built. Pilgrims still journeyed to the holy well, although its religious designation had changed. Some stayed on in the village, seeking protection of the church authorities. Then in the middle ages, the poor and elderly lived here on the charity of the pious. There were many such religious villages in Sardinia, offering refuge to the poor.

The village of San Salvatore near Cabras resembles in essence what those religious villages must have been like. San Salvatore is a vestige of Lawrence’s undiscovered Sardinia.Like Santa Cristina, it is built around a sacred well, but unlike Santa Christina, San Salvatore continues to have a life of its own… to be continued in Part 2 https://magiclibrarybomarzo.wordpress.com/2022/08/01/sardinia-uncaptured-2/

…

This is fascinating. The ancient Sardinian culture with its standing stonesyou sounds very Celtic. I can’t wait to read more.

LikeLike